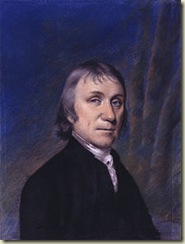

Last week NPR ran a story about a poem, reportedly one of the first pieces of animal rights literature. Ann Barbauld, an assistant in the lab of Joseph Priestly, penned it:

It was, after all, 1773, just a few years before Lexington, Concord and the Declaration of Independence. On both sides of the Atlantic, "inalienable rights" were a rallying cry, and Anna, a young wife and poet, decided to write a protest poem. She called it "The Mouse's Petition to Dr. Priestley, Found in the Trap where he had been Confined all Night."

NPR included commentary from a historian on the concept of “inalienable rights,” and an actress read the poem with great emotion.

Priestly himself gets a bit lost in their discussion:

There were lots of mice in Priestley's lab. He had made his reputation as one of the first scientists to identify oxygen. He studied mice to figure out what happens inside animals as they breathe. This meant he regularly opened them to examine lungs, veins, arteries, to see that blood changed color when it moved through lungs. And since tuberculosis -- or "consumption" -- was the scourge of that era, lung research seemed like a valuable thing to do.

Priestly described oxygen, photosynthesis, and carbonation. He also founded Unitarianism. His support of controversial ideas often necessitated moves to other countries or even continents; he died in the United States because he supported both the US and French revolutions.

Some of his most famous experiments are detailed at this web site. He collected oxygen and found that a container of it burned longer and kept mice alive longer than an identical container of air. He also demonstrated that plants can produce oxygen; a closed container would kill a mouse, but a plant in the same closed container allowed the mouse to live.

Priestly’s ongoing belief in phlogiston theory kept him from developing his observations to their full potential and eventually excluded him from mainstream science. Antoine Lavoisier eventually “discovered” oxygen as well and recognized it as an element, discrediting phlogiston theory along the way. These events led to the development of modern chemistry. The American Chemical Society arose from a commemoration of Priestly’s work a few years after his death.

Today, combustion is a chemical reaction. Air contains oxygen that enters our blood through our lungs. Plants renew oxygen in the air. All of these facts result, at least in part, from Priestly’s experiments with mice.

People and animals still die of lung diseases. We still have much to learn about the way bodies work. There are still questions we cannot answer without using animal models. Today, though, our animals get much more protection. Institutions that perform animal research supervise scientists and require protocols that use the lowest number of animals possible. Most laboratory animals come from commercial sources and are bred solely as research subjects; rats and mice are generally not trapped in the wild as they were in the 1700s. Experiments expected to end in the death of an animal, such as Priestly’s, require extra levels of justification and supervision. While most animals do succumb to experimental efforts, death most often occurs under anesthesia or via another approved method of euthanasia. Food and water are provided. Environments are enriched. Pain and distress are minimized, as required by law.

Animal research remains an important tool for understanding biology and disease. Without it, progress in a number of disorders will be slowed or stopped. I am glad NPR told me about this historically important piece of literature; I just wish they would have pointed out the importance of Priestly’s experiments; surely they justify the loss of some mice.

No comments:

Post a Comment