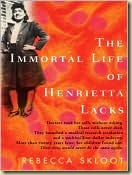

I just completed The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, by Rebecca Skloot. It is a must-read for a number of groups, including those who study cancer, those who use cultured cells, anyone who performs clinical research, and anyone in healthcare.

I read fast, but especially in this case. Many of my online peers had pre-release copies and have blogged about the book for weeks. I also wanted a review for the March issue of ASN Kidney News with its special section on kidney disease research issues.

Immortal Life addresses many issues relevant to medicine and life in the 20th century. Poverty and racism and access all influenced Henrietta’s (I feel like I’m on a first-name basis after reading her story) care and that of her children. As someone who works in basic science (and, for a couple of years, in a carcinogenesis laboratory), the history of tissue culture was fascinating. I learned far more about the development of human subject protection than I did from my required clinical research training, and in a far more memorable way.

Ms. Skloot’s time spent with Henrietta’s family paid off in the narrative in a big way. Henrietta is no longer just someone who died of cervical cancer; she becomes a beautiful, lively woman who dressed well and kept her finger- and toe-nails perfectly manicured in flaming red (a trait with which I can easily identify). Her story and those of her family, in particular her daughters, also drive home their mistrust of the medical and science professions.

The development of their mistrust of the biomedical enterprise brought me back to a book from last summer, Unscientific America. Mooney and Kirshenbaum argue that the public mistrusts scientists because we are, in general, so bad at communicating with them. Examples of bad communication abound in Immortal Life; even when supposedly getting “informed consent” for testing on Henrietta’s descendents, it is clear the family has no clue what will be done with their blood. When Deborah, Henrietta’s daughter, first visits a laboratory at Hopkins to find out what happens with her mother’s cells, the investigator gives her an autographed copy of a text he wrote on genetics, something she cannot fathom. (A second visit in the 21st century works out better and diffuses some of the concern and anger of the family members.)

I had a different argument after Unscientifc America, namely that scientists and other biomedical researchers had lost the public trust:

We were promised “better living through chemistry.” While DDT could zap mosquitoes and eliminate malaria, it had detrimental effects on the environment. The green revolution that has allowed the overpopulated world to be fed has taken its toll on the land. People now mistrust the agribusiness industry. In medicine, it seems like papers trumpet polar opposite results; the public can’t decide what to believe, and thus decides to believe no one.

Add to that perception experiences like those of the Lacks family, especially her daughter Elsie, and others of the time. More than a decade after Nuremburg researchers were still injecting people with cancer cells without telling them what they were. The Tuskegee syphilis experiments had just come to light. Today, when institutions have offices devoted to patents and business discovery development, patients donating tissues with appropriate informed consent want to know the value of their cells.

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks reads like a novel but is absolutely true. It is must-reading for those involved in medicine or science, especially researchers working with human subjects (what a depersonalized term!). I believe it might help the general public as well, showing them the evolution of protection of their rights and dignity should they choose to participate in biomedical research.

This book could be a first step toward regaining some public trust.

And I swear I will not complain (at least not as much) the next time I have to answer all of those questions for our Institutional Review Board.

No comments:

Post a Comment